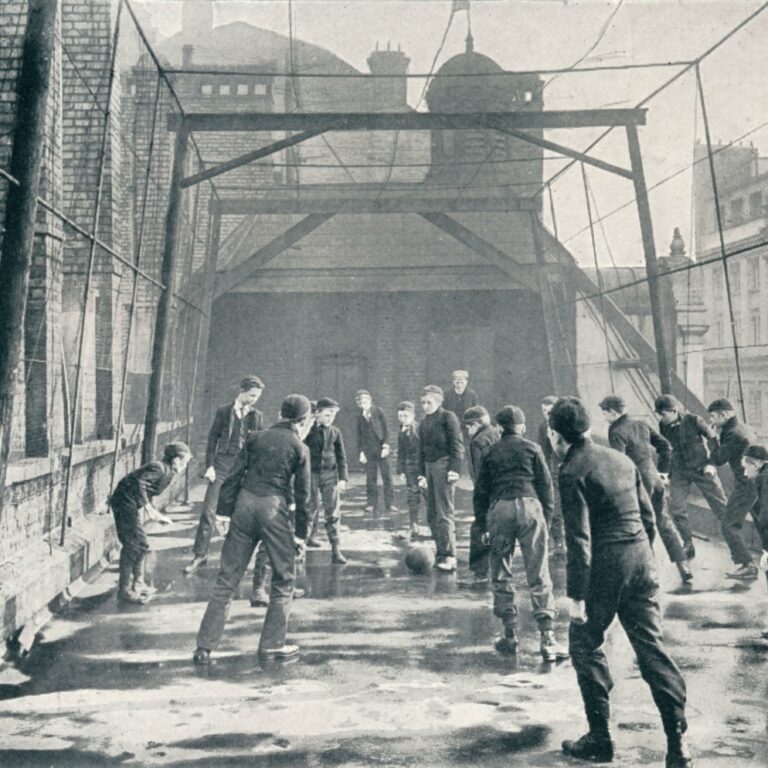

St Paul’s Cathedral School has existed for over nine hundred years. It has been on its present site for a mere forty. Now a co-educational school for around 285 pupils from four to thirteen, it was originally founded for only eight boys, educated free in exchange for singing the daily office in the cathedral.

Its Beginnings

There has been a song school associated with St Paul’s Cathedral since its foundation in 604. However, nothing much is known about it until the twelfth century when in 1127, Richard de Belmeis, Bishop of London re-founded it for the choristers, 8 boys in need of alms who were provided with a home and education in return for singing the Cathedral. Their house stood almost on the site of the Carter Lane School. St Paul’s seems to have been the earliest cathedral to house its choristers instead of boarding them out with canons. In 1263 the boys were in the charge of an almoner who, as ‘Master of the Children’ was responsible for their education, as well as looking after them.

The Fourteenth Century

In 1315 William of Tolleshunt was made almoner and was given a house near St Paul’s by Bishop Richard of Newport to accommodate the choristers. William of Tolleshunt died in 1329 and left a shilling to each of the senior choristers and 6 pence to each of the juniors. He also left £1, six shillings and eight pence to provide them with shoes in return for singing twice daily the psalm De Profundis, the Lord’s Prayer and Ave Maria for his soul.

Later in the fourteenth century the almoner recorded that if a clerk was not kept to teach the boys grammar they must go to St Paul’s school, the predecessor of Colet’s school, for their lessons. Gradually two schools emerged, the Choir School and the Grammar School. For many years they co-existed happily, the choristers graduating to the Grammar school to finish their education, until the latter was re-founded by Dean Colet in 1511 and became St Paul’s School which is now in Barnes and has only a tentative connection with the Cathedral.

Choristers Act at Court

In the sixteenth century, the school was more famous for its acting than its singing. Acting had always been a popular pastime with the ‘Children of St Paul’s’, and at one time they petitioned the king to prohibit certain amateurs from acting their plays. The choristers became such a favourite band of players that they were frequently asked to act at court, performing regularly at Greenwich Palace before Queen Elizabeth 1, and incurring the wrath of Shakespeare and his professional company just over the river. In Hamlet (Act 2, Scene 2), Rosencrantz rails against the nest of ‘little eyases’ (little eagles) who are roundly applauded for their histrionic efforts:

But there is, sir, an eyrie of children, little eyases, that cry out on the top of question and are most tyrannically clapped for ’t. These are now the fashion, and so berattle the common stages – so they call them – that many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose quills and dare scarce come thither.

Dean Newell instructed the master of the choristers, Thomas Gyles, to teach his boys writing, music and the catechism, and send them to St Paul’s School to learn grammar and read good books.

The small oil etching below depicts Bishop Dr John King of London preaching to James the First and his queen at Paul’s Cross in 1620, and in the background are twelve little white blobs – the choristers. Acting came to an end in 1626 as there had been instances of the kidnapping of boys to other groups of players. It was also thought to

The Restoration and the Great Fire of London

At the time of the Restoration it was with great difficulty that a sufficient number of suitable boys could be found to establish a new choral tradition and the choristers had a somewhat chequered history. The money set aside to run choir schools and feed the choristers was often sneakily redistributed into other funding areas so that organists could barely earn a living and the boys were left largely to their own devices. To add to the problem, the Great Fire of London in 1665 destroyed the cathedral and also Dean Colet’s school where the choristers had been educated during the war. A fortunate appointment however had been made in Dean John Barwick, himself a keen musician who worked hard to restore order out of chaos and even managed to gather a choir of boys. Whether it was for those boys or for another group is uncertain, but an almonry was built about 1666 in Pardon Churchyard. It was very soon demolished for fire reasons, being so near to the cathedral.

After the Great Fire of London, Christopher Wren was selected as the architect of the new St Paul’s, the previous building having been completely destroyed. Although the architect of many fine buildings, Wren is particularly known for his design for St Paul’s which is the only Renaissance cathedral in England. Michael Wise, celebrated church composer, became almoner and master of the boys in 1686 and John Blow, even more celebrated, one year later. In 1697 Charles King held the appointment while Jonathan Battishill, later to become a ‘great’ in church music, was one of his choristers.

King was popular with the boys as apparently he never used the cane!

The Eighteenth Century

The choristers and almoner all moved to a house in the parish of St Benet until Charles King’s death in 1748. His successor was William Savage and the boys lived with him at Bakehouse Court until he was dismissed for misconduct. Meanwhile, Maurice Greene, former chorister and composer of much well known church music, had been appointed organist and remained until his death in 1755. William Savage was succeeded as almoner by John Bellamy, followed shortly after by John Sale who found that his allowance for the boys was totally inadequate. He asked the Dean and Chapter for a larger allowance but was refused. He had no alternative but to turn the boys out onto the streets. Some went to their own homes, but those who lived further away were virtually homeless; as long as they turned up for service and practice, for the rest of the day there was not a soul who cared where they were or what they were up to, and of course they had no education at all.

Maria Hackett

In the 19th century, Maria Hackett began her great work for choristers, working to improve their welfare. Maria’s interest in the Choristers began in 1810, when she enrolled her seven-year-old orphaned cousin, Henry Wintle as a Chorister at St Paul’s. At that time, the boys were not receiving proper housing, education or supervision. They were routinely hired out, for the singing master’s profit, to perform at public concerts and dinners with little thought for their safety or welfare.

The archives of St Paul’s held the key to determining the Cathedral authorities’ responsibilities towards the Choristers, and after in-depth research, Maria sent the Bishop of London a detailed account of her findings in January 1811. His evasive reply prompted her to write to other Cathedral dignitaries, but with no more success. In 1813 she, George Capper, and her half-brothers initiated legal proceedings that had to be abandoned prematurely because of expense.

Hackett continued her letter writing and research, and her efforts began to meet with success. She published her Correspondence and evidences respecting the ancient collegiate school attached to St Paul’s Cathedral (1811–32). She also began to investigate all the choral foundations of England and Wales, resulting in the publication of a ‘Brief account of cathedral and collegiate schools with an abstract of their statutes and endowments’ (1827).

A day in the life of a chorister in 1836 looked like this: Up at 7.30am (8am in winter) and choir practice before breakfast (milk, bread, and butter). Mattins at 9.45am, and music and singing practice from 11am to 2pm. On one morning of the week, six boys were given an Italian lesson, paid for by Miss Maria Hackett. Dinner was at 3pm (meat, vegetables and half a pint of beer). Evensong was at 3.15, and after a break the boys had lessons from 5.30 to 8pm. Supper was bread, butter and beer and bedtime was 9pm – or as late as midnight if it was an oratorio evening.

The Choristers regularly enjoyed treats brought by Maria when she came to the Cathedral to worship. For more than fifty years, she made autumn visits to other choral foundations, calling on each at least once in three years, noting the names of the Choristers in her diary and presenting to each boy with a book, a purse, and a new shilling. In 1845, Archdeacon William Hale became the almoner and the boys lived under his care in the Chapter House. Between 1848 and 1875 there was again no boarding. The boys attended the school in the Precentor’s house at 1 Amen Court daily and used the Lord Mayor’s vestry in the Cathedral as their practice room.

After many letters to the bishop, the dean and other dignitaries, Maria’s lifelong efforts were realised when, at the age of 90 she was shown the new St Paul’s Choir school in Carter Lane. Maria died at 91 and her funeral at Highgate Cemetery was attended by the choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, and in 1877 a memorial plaque was erected, paid for by choristers up and down the country.

After his voice broke he was awarded the Merchant Taylors’ Musical Scholarship, and began studying with his father to become an organist. He was church organist for Christ Church, Preston. He also worked for Manchester & Liverpool District Banking Co.

After his voice broke he was awarded the Merchant Taylors’ Musical Scholarship, and began studying with his father to become an organist. He was church organist for Christ Church, Preston. He also worked for Manchester & Liverpool District Banking Co.

At the outbreak of the Second World War the choristers were evacuated to Truro, where they sang services in Truro Cathedral. The juniors were housed in Trewinard Court, the boarding house of Truro Cathedral School, and the seniors were boarded out in the town. Dr John Dykes Bower, organist of St Paul’s and his assistant Dr Douglas Hopkins took it in turns to go down to Truro for a month at a time and in between, a month at St Paul’s where the lay clerks were singing the services. The Choristers were brought up to London occasionally for a short spell when it was thought to be safe.

At the outbreak of the Second World War the choristers were evacuated to Truro, where they sang services in Truro Cathedral. The juniors were housed in Trewinard Court, the boarding house of Truro Cathedral School, and the seniors were boarded out in the town. Dr John Dykes Bower, organist of St Paul’s and his assistant Dr Douglas Hopkins took it in turns to go down to Truro for a month at a time and in between, a month at St Paul’s where the lay clerks were singing the services. The Choristers were brought up to London occasionally for a short spell when it was thought to be safe.